Healthy Ram

Published in: Blog | Category: Humor

Last Saturday, I attended a lecture hosted by a Mutual Fund Management company I recently switched to — still chasing that elusive miracle formula that promises to protect my investment and, hopefully, return at least the principal in five years. Not that inflation cares.

Until I returned to India, I had little clue where my money had gone, guided as it was by financial wizards selling magical funds and Unit Linked Plans. But now that time is on my side (or at least refusing to budge), I attend these free “Gyan” sessions in the hope of learning how to lose my money more intelligently.

The lecture sounded like standard fare — charts, predictions, disclaimers — but what caught my eye was the phrase “High Tea will be served.” And who says no to that?

The Company I Keep (and Bring)

Determined to take full advantage of the invitation and test their financial wisdom, I brought along Smart Sulekhika and her sister. I even extended the invite to my in-laws. To my surprise, they declined the free meal. Even more surprising, my mother-in-law tried persuading her husband to attend — he, the family’s retired (and battle-scarred) financial wizard, who refused, having invested and lost enough to know soggy sandwiches aren’t worth another risk.

The Freebie Magnet

Now, getting Smart Sulekhika out of the house at 5:30 PM is no small feat. She lives by her own calendar — one where lunch at 4 PM is normal. But “High Tea”? That’s a language she understands. Her appetite for complimentary things is legendary.

Back in China, hotels offered free breakfast, and each time she joined me on inspection trips, I feared the hotel might rethink its generous policy by the end of our stay.

Breakfast Wars – Global Edition

Speaking of free meals, the Chinese are unmatched in their enthusiasm. Hotel breakfast starts at dawn. Arrive late (as any Indian would), and you’ll be greeted by a battlefield: littered napkins, emptied dishes, and buffet pans echoing stories of what once was.

We think we’re different — caste, race, culture, religion — but strip it down to survival instincts, and we’re the same. Case in point: in drought-hit Maharashtra, police had to guard water stations after a murder over water. Scarcity changes everything.

The Free Breakfast Chronicles

At the company I briefly worked for in the U.S., free breakfast was offered on Fridays. The attendance that day? Flawless. Even the unwell dragged themselves in. No one wanted to wait six more days for another free bite.

There are countless tales of how humans react to free food, but those are stories for another day. For now, let’s get back to our High Tea event…

Smart Sulekhika, the Crowd, and the Queue

Let me pause here to introduce a recurring character in my blogs — Smart Sulekhika. That’s the moniker I use for my better half. I coined it back when I was blogging on Sulekha.com, a platform that had more women than men, and most of them either wrote exceptionally well or at least compensated with verbosity.

In my writing journey, I haven’t interacted with many fellow writers — male or female — mostly because, as a sailor without internet access, my words stayed confined to personal diaries. But the woman I married? She could outwit most of them. She doesn’t read what I write (a safe blessing), but to honor her influence and presence, I created the persona of Smart Sulekhika.

Why the name? Well, “lekhak” in Hindi means writer, “lekhika” its feminine form, and “sulekh” means beautiful writing. Add “Smart” — and there you have it: a fitting title for the star character in many of my posts. Over time, the name stuck, and anyone from the Sulekha days knew instantly who I was referring to.

“What time should I ask D… to be ready?” snapped Smart Sulekhika.

I did a quick mental calculation. “Half an hour for her, and another half for her sister — though she doesn’t live with us. Better keep a buffer — let’s budget an hour.” I glanced at the invitation. “The presentation begins at 5 p.m. and is followed by High Tea, though they haven’t mentioned when exactly that starts.”

“Presentations don’t usually last more than two hours,” I reasoned aloud. “We should aim to reach by six — just in time to avoid looking like we only came for the food.” Though in my heart, I knew it would be closer to 6:30. Still, hopefully not later than 7.

We reached around 6:30 p.m. — it was like arriving at a cinema with a big, red “House Full” board waiting for you. We managed to grab a couple of the overflow seats lining the wall. That put us close to the speaker, but nearly at a right angle to the screen. And thanks to a wide support column conveniently positioned in my line of vision — a perfect metaphor for my financial skepticism — I saw even less.

I could hear just fine, as the speaker had a mic and a high-powered amplifier right above me. But after years of experience, I’ve learned not to trust this sense organ entirely. I couldn’t catch the questions from the audience, but Smart Sulekhika — who, like always, doubled as my external hearing aid — leaned in to whisper clarifications. This was in stark contrast to our conversations at home, where she yells to ensure I hear her and then complains that I’ve completely misunderstood.

From the size of the crowd, it was obvious we were late. Yet the hosts greeted us politely. The speaker knew his subject and delivered with flair, though let’s be honest — he wasn’t Warren Buffett. Not that anyone cared. The only buffet people were truly interested in was the one set up for High Tea.

Q&A sessions caused further delays. The room grew restless. People were clearly more interested in testing the company’s budget against the strength of freeloaders than in financial instruments. Wanting to seem engaged, I tossed a complex question at the speaker. He answered well, but in doing so, accidentally revealed to Smart Sulekhika a detail about one of my past financial misadventures — a mistake I would regret far more than any market loss.

Eventually, the speaker wrapped up and apologized for the delay in starting the small feast. What followed was pure chaos — a stampede of famished attendees surging toward the buffet. In that instant, Smart Sulekhika and her sister deserted me like optimism deserts a crumbling investment portfolio.

Fortunately, the crowd was polite enough to let the women and children go first. Still, within minutes, a queue of mythical proportions formed. It didn’t budge for what seemed like an hour. Women and children weren’t in the queue — they simply orbited it, acting as if queues were for mere mortals.

Behind me, a few latecomers gave me some strange solace — at least I wasn’t the last one. The man ahead muttered, “These people have incredible appetites. They’re loading up plates like there’s no tomorrow.”

“What?” said the man behind me. “This is nothing. You should see the folks in Amritsar — they know how to eat!”

He repeated it for emphasis.

I smiled. Amritsar — my birthplace. I nodded in agreement and turned to acknowledge him. He had a belly that could be rented out for billboard space.

And this, dear readers, is Healthy Ram — the title character of my tale, finally making his grand entrance.

Lassi, Legends, and the Rise of Healthy Ram

Standing in line for the buffet, conversation turned from the mundane to the mouthwatering.

“There are shops in Amritsar where they serve preparations in copious quantities,” he began, clearly warming up. “Every dish — be it Daal Makhani or Butter Chicken — comes with a fist-sized dollop of freshly skimmed butter floating on top.”

He was savoring them vicariously, but as he noticed I hadn’t reacted with the awe he expected, he doubled down. To save my jaw from actually dropping (which might have needed surgical intervention to reset), I clamped my lips tight. Once I’d frozen the lower half of my face, I managed to say, in a voice so muffled and alien that even I didn’t recognize it:

“I was born in Amritsar.”

Translation: Spare me the fairy tales, I’ve lived the legend.

Indeed, I had. As a child, those tales of generosity were true — but I now doubt whether the magnanimity of yesteryears has survived the avarice of today. The few who’ve tried to preserve ancestral recipes, with the same love and munificence, are either shutting shop or compromising quality.

Some exceptions linger — like Bhudania Brothers or Laxmi Narayan Chiwda of Pune — but they’re vanishing as rapidly as certain birds and fish species. People have become health-conscious and time-strapped. The bonhomie of old is missing. After a long workday, no one wants to navigate narrow lanes and parking chaos just for a taste of “Kake ka Tandoori Chicken” — not when you can tap an app and get dozens of Kakes delivering piping hot versions to your door in minutes. The purists, the connoisseurs, are now an endangered species themselves.

Lassi ka Gilas

He broke my reverie with an enthusiastic swing of his forearm. “You get these giant Lassi ke Gilaas — have you seen those tapering brass tumblers?”

“Yes,” I said, to his visible disappointment. His face dimmed, his pride in revealing rare culinary wisdom dashed.

“Kade wala Gilas,” I added, recalling the old brass tumblers — beautifully engraved with floral motifs, narrow at the base with an inverted cup-shaped support, and capable of holding more than a litre of liquid. Back in the 60s, breakfast often meant a tall glass of freshly churned lassi with blobs of butter floating on top — paired with a besan ka parantha, I added smugly.

“No, no,” he corrected with a wave. “It should be a five-grain mix — besan, soybean, wheat, barley, and millet.”

He counted them on his fingers with the confidence of a seasoned dietitian.

I thought to myself — this man would have thrived in China, where we had such a horrid time just finding wheat flour. What we got was maida, the refined, bran-less wheat flour that doesn’t lend itself well to chapatis. And my wife, not being one for culinary experiments, produced chapatis that came out more like tandoori rotis. Rolling a roti from maida requires wizardry — what you usually end up with is a naan.

(Though I joke, let it be said: I neither complained nor starved. The fact that I’m here writing this proves I survived her culinary minimalism — and possibly even developed a robust immunity in the process.)

Chapati, Phulka, Tandoori Roti, and Naan

He now declared proudly, “I have two glasses of lassi every day.”

“And I drink plenty of other fluids too — juices, cold drinks…”

“Lassi makes you drowsy,” I said.

“Not me,” he retorted. “I’m alert as a hawk.”

A hawk, perhaps, with very sleepy eyes.

“I also eat roasted black grams,” he said.

“They’re packed with nutrients,” I replied, trying to be encouraging.

“You must roast them with heeng,” he insisted. “You can even get them at Haldi Ram’s.”

He said the name with the kind of reverence usually reserved for spiritual gurus or cricket legends. His eyes lit up.

Son Papadi… Ahahaha, he exclaimed, smacking the air.

The wattage in his expression soared to dangerously high levels — enough to trigger voltage fluctuation in an entire colony. I worried briefly that the next phase of his enthusiasm might trip a circuit, blow a fuse, and plunge all nearby ACs and refrigerators into darkness.

Though he couched his recommendations in health-conscious language, his bulk did little to inspire confidence in the message. Yet I couldn’t help but admire his devotion to food — the lengths he went to obtain what he liked, the poetry with which he spoke about it.

And then came his final flourish:

“Haldi Ram,” he said, with absolute conviction, “should actually be called Healthy Ram.”

I was speechless.

He went on, “You can buy anything from Haldi Ram with your eyes closed and eat it without fear.” Then he added, dreamily: “The assorted cashews, the almonds… My Gawd…”

He kissed his fingers and sent a French kiss flying through the air, which I suspect was aimed at Mother Annapurna herself.

Visuals for This Chapter

Since I can’t include images here directly, here’s a description of what the visuals in this section should portray:

- Lassi ka Gilas – A classic brass tumbler with floral engraving, wide at the top, narrow at the base with a cup-shaped stand — filled to the brim with thick, white lassi and a dollop of butter floating on top.

- Chapati (Phulka) – A soft, puffed, golden-brown Indian flatbread, made on a traditional tawa.

- Tandoori Roti – Thicker, cooked in a clay oven, with a shiny knob of melting butter on it.

- Tandoori Naan – Flatter, broader, blistered from tandoor heat, possibly sprinkled with sesame or garlic.

- Son Papadi – The flaky, cube-shaped Indian sweet that disintegrates into sugary threads with a single touch — placed neatly in paper cups.

Delicious, Superb....

“Delicious, superb, I don’t have the words to express,” he said, eyes gleaming. “As if each individual nut is handpicked and selected. And the Namkeen—no oil on the fingers, just the right amount for that perfect crispness.”

“You can get any product you want easily from Patanjali Stores,” I interjected, “they’re mushrooming like mistletoes after rain.”

He looked at me, confused. And before he could respond, I realized my folly—mistaking Haldi Ram for Baba Ramdev. I corrected myself quickly, mumbling something about how even Patanjali produces health products of decent quality, though in truth, I have no idea what they even sell.

But he hadn’t registered my blunder. He was back in his reverie, dreamily savoring the taste of roasted almonds. He is one of those rare people who must always be either eating or thinking about eating. A colleague once said there are only two kinds of people in the world: those who live to eat, and those who eat to live. He was clearly the former. I am most certainly the latter.

After momentarily returning from his almond-laced dreams, he declared:

“I take a big glass of milk in the morning.”

I paused. He had earlier mentioned having two glasses of Lassi in the morning. Surely, one cannot have both? Unless, of course, his morning stretches from dawn to noon, which, given his food schedule, might very well be the case.

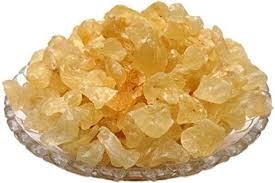

“At night I soak some almonds and Gond Katira in water,” he added.

“Do you know what Gond Katira is?” he asked, testing my knowledge.

My Google search tells me it’s called Tragacanth Gum.

Image: Gond Katira (Tragacanth Gum), dried and soaked form

“Yes,” I replied confidently. “Our mother used to put it in Pinnis.”

Image: Pinni – A Punjabi winter sweet made with roasted grain flour and dry fruits

Pinnis are ball-shaped confections typically made in the winter. I remember my father grinding soaked dal with a mortar and pestle—there were no electric grinders then. He would help roast the ingredients in desi ghee in a large kadai. It took a lot of effort to stir the thick mixture. That gives you an idea of his strength—on Sundays, he’d do a hundred sit-stand-ups with all four of us children perched on his shoulders. Our youngest brother must’ve been at least three years old to be able to sit holding on.

The cooked mixture would be rolled into laddoo-sized balls for us to eat all through the long Himalayan winters.

My father also made pickles. He knew the recipes—though I never learned the art. And since SmartSulekhika doesn’t like pickles, I’ve never had to revisit those memory files, which are stored not in recipes but in visuals—ingredients, sunlight, masala-stained hands. With YouTube’s help, maybe I could recreate “Mother’s Special,” but SmartSulekhika isn’t interested.

Image: Sevaiyaan (vermicelli), commonly used in desserts

Now, SmartSulekhika does have a sweet tooth. Soon after marriage, during our early days of experimenting with domestic life, she once wanted to have Sevaiyaan. Neither of us knew how to make them. But I believed that cooking is just common sense.

We bought the roasted vermicelli, but I toasted them again in ghee (I think?), added milk or water (I can’t remember which), and somehow ended up with something that resembled halwa. I would’ve eaten it gladly—taste over presentation, always—but she was unimpressed. For her, food must taste good and look good. From that day on, I’ve never been asked to assist in the kitchen. Nor do I offer. My mother’s wisdom rings in my ears:

“Ek chup, sau sukh.”

(Silence brings a hundred joys.)

Now, the kitchen is a No Entry Zone for me. If I ever have to enter while she’s cooking, she freezes mid-action, eyes locked on me like a surveillance camera. If our eyes meet, her expression is like a bull staring down a matador.

Image: Matador being gored by a bull – a metaphor for entering forbidden territory

Well, perhaps not a matador—more like a mouse that has stumbled into a lioness’s den. Yes, that’s a better metaphor. The kind where the woman and mouse eye each other warily—both frightened but equally determined.

Let’s get back to Mr. Glutton.

My thoughts were interrupted by a fresh torrent of wisdom from him—rare and unfiltered, like Vedic Shruti, passed down from teacher to disciple. Alas, my Shruti is weak, and my Stuti (praise) is even weaker. I’m a cynic.

Image: Yarsta Gunbu (Caterpillar fungus) – the world’s most expensive food

“What you’ve been eating is just tree gum or paper glue,” he declared solemnly, not even bothering to ask me what we used. His tone was as if I had claimed to eat Yartsa Gunbu—the dead caterpillar fungus prized in Tibet—when in fact, I’d been chewing rubber bands.

I felt humbled. Or rather, I meekly played the part, which suits me better. A small part of me even wondered—had being fed paper glue as a child made me stick to Sulekhika the way I do?

“When you soak a small lump of it overnight, it swells up to the size of a ball,” he added.

A table tennis ball, I presumed. Surely not a lawn tennis one.

Halloa!—as Sherlock Holmes would say in Arthur Conan Doyle’s tales, I had a eureka moment.

My Google search reads:

“Gond Katira is a viscous, odourless, tasteless, water-soluble mixture of polysaccharides obtained from the sap drained from the root of the plant and dried.”

Water-soluble! That’s the kicker.

So all these years, this foodie friend has been consuming fake Gond Katira—some tree gum peddled by crafty swindlers. I don’t know if it harmed him, but it’s certainly turned him into a giant, gelatinous version of the very thing he thought he was consuming.

About kalonji and Yartsa Gunbu

I was standing in a queue for a buffet when “Healthy Ram” queued up behind me. He wasted no time launching into his morning routine. “To my milk,” he declared, “I add a spoon of haldi (turmeric) and a few seeds of kalonji.”

Kalonji? My eyes widened so much they almost popped out. Just then, a small object bounced near my feet. For a moment, I panicked — had my eyeballs fallen out? I quickly checked: both were still in place. Relieved, I looked again. Perhaps it was some gond katira that had fallen from Ram’s kurta pocket? Thankfully, my anxiety was short-lived — a child appeared, chasing a tennis ball.

The mention of kalonji triggered a faint memory. My mother’s pickling recipes had buried it somewhere deep in my subconscious. I dug into my mental archives and recalled that kalonji were tiny black seeds, usually tossed into jars of spicy homemade pickles. I won’t get into their benefits here — there are plenty of articles online for that — but according to Healthy Ram, these seeds are miracle workers.

If you start Googling these things, you’ll notice a pattern — every root, leaf, or speck of dust on Earth is apparently a sanjivani booti, a magical cure-all. Some are rediscovered by chance; others survive through oral tradition. But there’s always someone who swears by their power, and often, thousands of loyal users backing them up.

I often wonder: did all those brilliant writers of the past have encyclopedic memories? Or were they just as curious and accidental in their discoveries as I am? I don’t claim to have deep knowledge, but I do thank my curiosity — it refuses to leave anything unfamiliar alone. Whenever a strange word or concept lands in my lap, I end up chasing it like that child with the tennis ball.

Take Yartsa Gunbu, the caterpillar fungus I mentioned in a previous blog. Let me tell you a little more…

Yin And Yang

Take Yartsa Gunbu, the caterpillar fungus I mentioned in a previous blog. Here’s a bit more about this peculiar wonder of nature.

The image I found online gives a sense of just how small and elusive it is — people scour harsh Himalayan altitudes just to find it. It’s a parasite, really. It infects caterpillars that burrow underground in the Tibetan Plateau and Himalayan regions at elevations between 3,000 and 5,000 meters. These caterpillars feed on roots beneath the surface and are most vulnerable when they shed their skin in late summer — right when the fungus releases its spores.

Chinese traditional medicine considers it potent because it represents a rare fusion of life forms — a plant feeding on an animal — seen as a balance of yin and yang. Fascinating, isn’t it? If you’re curious, you can read the full article here:

Yin And Yang

https://www.zmescience.com/medicine/alternative-medicine-medicine/expensive-fungus-world-dead-caterpillar-sells-50000-usd-pound

Now, back to the idea that some discoveries happen by chance.

I, too, have always been a bit of a hopeful explorer — driven by the idea that the next big discovery might just fall into my lap. From childhood, I’ve had this odd curiosity. Unfortunately, nothing earth-shattering has come of it yet — except for marrying SmartSulekhika, a serendipitous find indeed — but I haven’t given up.

One day, while parked under the shade of a tree, I remembered reading somewhere that boiling Neem leaves in water produces a highly beneficial drink. The tree above looked like a Neem tree — or so I thought — so I plucked a few leaves, brought them home, boiled them, and drank the extract. It wasn’t terribly bitter, just bitterish, and I told myself I could get used to it.

The next day, I returned to the same spot for another batch of leaves. As I reached up, a woman — likely the wife of the chaiwala nearby — saw me and immediately guessed what I was up to.

“Arre sahib, ye kya kar rahe hain? Ye neem ka ped nahi hai!”

(“Sir, what are you doing? This isn’t a Neem tree!”)

She even told me the name of the tree, which I promptly forgot in my embarrassment. But I was amazed — not just by her botanical knowledge, but by how accurately she had read my mind. I still don’t know what kind of leaves I had boiled the day before, or whether that potion did anything good (or bad) to me. But I silently thanked the Chandigarh administration for not planting poisonous trees all over the city — otherwise, curious souls like me might have been wiped out long ago.

Driving home, I thought of the massive Neem tree right outside my in-laws’ house. That one, I’m assured, is Neem — my wife said so. It’s only a five-minute walk from our home. But another thought quickly replaced it: if I ever tried to pluck its leaves, I’d have to face a far more bitter consequence — a sermon from my mother-in-law, delivered with laser-sharp precision.

Sometimes I wonder why God made so many tree leaves look so alike. Was He running out of ideas?

Sadly, the concoction I drank didn’t ignite any miraculous effects — not even a warm flush of energy. If it had, maybe I’d have stumbled onto a breakthrough aphrodisiac, a rival to Yartsa Gunbu. I could have patented it, made my millions, and then renounced it all to wander the Himalayas in search of life’s true meaning. What a twist that would have been — leaving behind my fortune while others still scrambled over frozen slopes for their shot at happiness in fungus form.

Stretching the Story

My habit of stretching stories until the reader begins to groan hasn’t changed—though times certainly have. Even here on Sulekha, things are not what they used to be. Blogging is practically extinct. People don’t even read long WhatsApp messages anymore. Twitter is now the trend, but as the saying goes: old habits die hard. I would modify it to: old people die, with their old habits still intact.

I believe we all live our lives within a time slot assigned to us. We may adapt to changing times, learn the new rules, maybe even play by them, but we still feel most at home when we slip back into our old groove. Give me a pen and a scrap of paper even today, and I promise the two lines I scribble there will feel more beautiful than the entire paragraph I type here—despite the aid of a Google dictionary and an entire digital literary world at my disposal.

Kishore Kumar once sang it best:

“Koi lauta de mere beete hue din,

Beete hue din woh mere, pyaare pal chin.”

(If only someone could return my lost days, those cherished moments of the past…)

While I listened with vague interest to his magical health potions and miracle routines, I refrained from mentioning my own misadventures—like the time I came dangerously close to discovering an alleged “herbal Viagra.” But now, the glow in his eyes was fading. The trays on the buffet table ahead looked ominously empty. He was showing the first signs of panic, as if his culinary dreams were slipping away, one missing samosa at a time.

He stepped out of the queue for a quick reconnaissance mission. After confirming that the caterers were dutifully refilling the emptied pans, he returned—reassured and crunching a samosa he’d snatched during his patrol.

Once reinstated in line, he resumed his monologue about the elaborate preparations and rituals involved in his daily diet. I listened with growing awe at the variety and intricacy of his food knowledge. But the nagging question in my mind remained: who on earth was doing all this for him? He certainly didn’t seem like the sort to be toiling over a stove himself. He must have an excellent wife. Or an extraordinary maid. Or, most likely, both.

How lucky some people are, I sighed inwardly, as jealousy slowly roasted my heart on a spit. I imagined my own lean frame beside his well-nourished bulk, my tongue rolling over parched lips. To soothe my pride, I offered myself a philosophical morsel: most ailments come from excess, I told my heart. Starvation, in small doses, is character building.

But then, he dropped a line that upended my smugness.

“Compared to what Pakistanis eat, we’re starving,” he said dramatically, diving back into daydream mode. Apparently, he’d recently been to Pakistan and was still spiritually digesting the parathas he’d eaten there.

“My host treated me to these huge parathas,” he said, stretching out his arms to demonstrate size. Given that he’s proportioned like a midsize SUV, the paratha he indicated could’ve doubled as a truck tyre. Or an XL rumali roti. He claimed it was a paratha, but I found it hard to digest—figuratively, if not literally.

“Wah!” he exclaimed, lost in the reverie. “Saag, gosht, and daal—all still cooked on traditional chullahs.” Meals were enjoyed on charpayees under the open sky, stars above, heritage below.

“Yes, yes,” I nodded, affirming his nostalgia. There was something admirable in how Pakistanis had preserved these culinary traditions—cooking the way our grandmothers did, without pressure cookers, microwave shortcuts, or calorie-counting apps. While we have health fads and Westernized icons dictating what’s good for us, they still embrace the full-fat, slow-cooked, soul-warming meals of yore.

Our ancestors, with little scientific input, still knew how to eat well. Tandoori rotis, parathas, daal, saag—all lovingly crowned with homemade butter. No fancy diagnostics. No ICUs. And yet, they lived fuller lives—if not longer ones.

Though I smiled politely throughout his account, some expression must have twisted on my face. Perhaps he read it as a sneer.

He suddenly snapped out of his trance, like a dog sensing an unfamiliar footstep.

“Do you doubt what I say?” he challenged.

“Oh no, no!” I quickly assured him. “On the contrary, I completely agree. In fact, I’ve been to Pakistan and seen those simple ways firsthand.”

He seemed partly satisfied. Though his eyes still darted between suspicion and pride, I had spoken the truth—or at least enough of it to protect my ear. Because in truth, I had agreed more out of fondness for my childhood than a celebration of gluttony. And partly, let’s be honest, out of fear. The man was twisting his kada and flexing his arm like he was about to deliver a well-aimed thwack.

The audiologist had once told me my left ear was more useless than my right. But even so, I didn’t want it rendered unfit for even a hearing aid. I turned my head to the right and studied a painting on the wall.

He didn’t like me turning away. He wanted my rapt attention. But as a former Merchant Navy man, I’m trained in strategic retreat when danger looms. I saw his hand playing with his steel bracelet again. Flex. Rotate. Crack.

“Jai Shri Ram,” I whispered in my head, while slipping my little finger into my ear and shaking it as if scratching an itch.

I tried to tell him again—“Actually, I’ve been to Pakistan…”—but what I really wanted to say was: Cut the hyperbole, my man. Or at least trim it enough to leave room for facts. But I held back. There’s only so long you can keep a finger in your ear while trying to look fascinated.

Meanwhile, the buffet queue had evaporated. At the table, the pans offered the usual suspects: sandwiches (bread triangles with cheese, cabbage, and mystery chicken), soggy fries, noodles, pakodas, sweet-and-sour veggie balls, and—thankfully—gulab jamuns.

I picked up a few items cautiously. It’s not for nothing that I had brought Smart Sulekhika and her sister along—if nothing else, they’re excellent judges of catering.

Just then, someone beside me, possibly a rival gourmand, looked at the gulab jamuns and asked, “Oh, ye bhi saath mein hi?”

Since this was a high tea and not a full-course dinner, there were no separate plates for dessert. A true dilemma for connoisseurs: placing gulab jamuns atop salty snacks could ruin the taste. But leaving them behind meant risking their extinction.

I noticed his overflowing plate and smiled with studied warmth.

“Abhi hi le lo,” I advised gently. “Baad mein shayad na milein.”

Because in life—and especially in buffet lines—timing is everything.