Arranging Milk for Goga

A tale of innocent schemes and a boy's mad love for milk

Goga was obsessed with milk. To say he loved it would be an understatement—he cherished it. Every conversation eventually circled back to doodh (milk), dahi (curd), lassi (buttermilk), or barfi (a milk-based sweet).

One sultry afternoon, while lounging outside the burji—an abandoned stone sentry post near the old jail—Goga leaned toward me with a conspiratorial look.

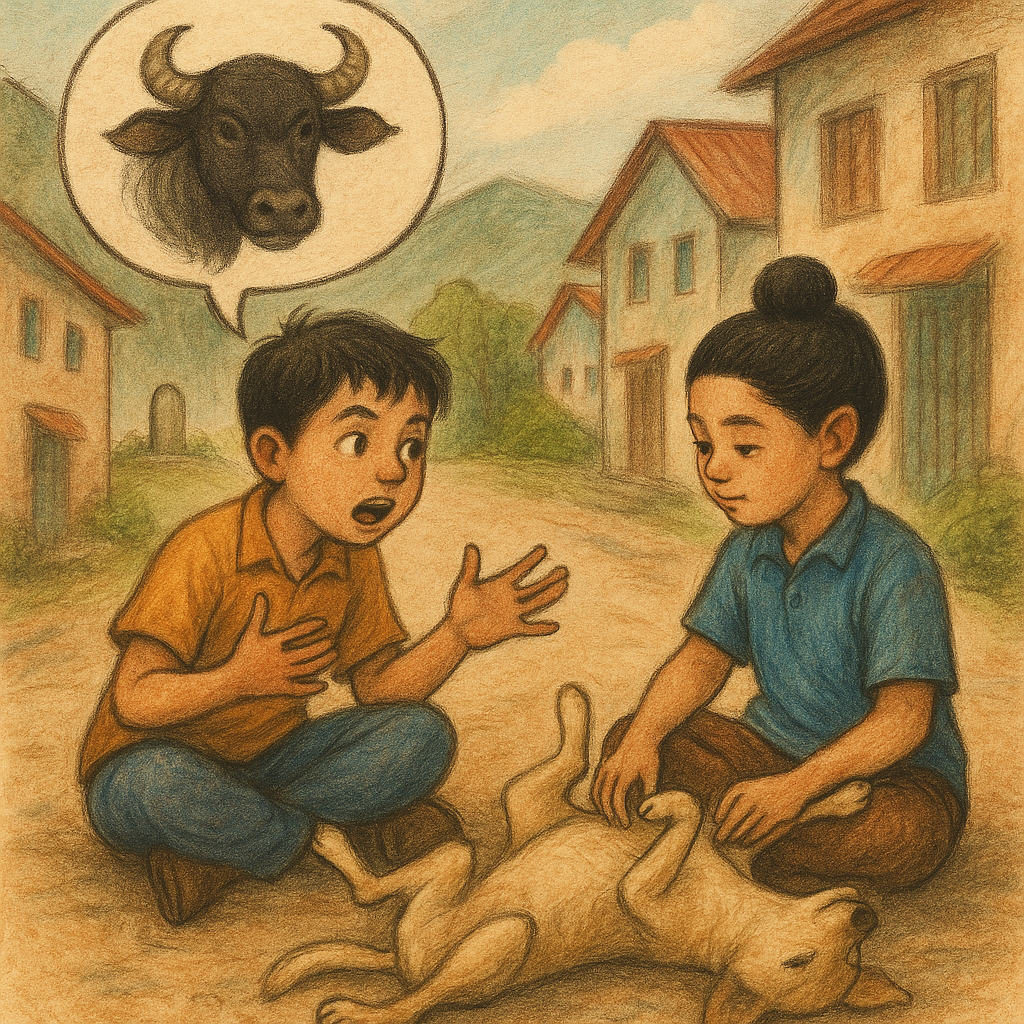

"Yaar, sadi mummy majh kyun nahi ban jandi?"

"Pal, why doesn’t our mother become a buffalo?"

I blinked. “What?”

He sat upright, serious now. “Think about it. If our mummy turned into a buffalo, we’d have fresh milk every day. Creamy, thick, never-ending milk.”

I couldn’t argue with that logic. Goga let out a dreamy sigh as if already floating in rivers of creamy lassi.

"But how can it happen?" I asked, half-dreading the answer.

"Sirf ek tareeka hai. Par kisi ko batana nahi."

"There’s only one way. But it has to stay a secret."

"I’m your friend. Tell me." I said.

"Chudail ton mangna pavega."

"We have to ask the chudail (female forest spirit) to do it."

I was horrified. Everyone knew that chudails haunted the forest past Kaithu. They had long, backward-turned feet, wild hair, and glowing eyes—and they devoured children who dared venture into their woods.

“She might catch us,” Goga added with a tone of fatalistic courage. “She might even eat us. But if she agrees...”

I nodded hesitantly. Goga’s convictions were hard to resist.

A few days later, near Dr. Sooraj Prakash’s dispensary in Upper Kaithu, Rosie the dog lay basking in the sun. She was one of a pair of golden-colored mongrels who always followed the doctor. That day, Rosie was stretched out near the canteen, tail twitching lazily.

Goga crouched near her, petting her ears. Then, gently, he pressed one of her nipples. A drop of white fluid beaded at the tip. He tasted it.

"Taste’s good... but not enough."

Rosie wagged her tail, unaware she’d just failed a taste test.

Then came the day we set out to meet the chudail.

Goga had written a solemn petition on a scrap of ruled paper:

“Meri mummy ko bhains bana do.”

“Please turn my mother into a buffalo.”

We walked deep into the pine forest, clutching that strange prayer like a sacred offering. As the shadows thickened and pine needles crunched beneath our feet, every sound seemed magnified—cracking twigs, whispering wind, the distant screech of a bird.

We found a clearing with a moss-covered mound that looked like a forgotten grave. Goga solemnly placed the note atop it and weighed it down with a rock.

Suddenly, a metallic door creaked in the distance—perhaps a corrugated tin public toilet swinging in the wind. But to us, it was the chudail responding.

We ran. I stumbled. A sharp branch—or maybe a cursed bone—pierced my foot. I cried out in pain.

"Chudail ki haddi hai! Kisi ko mat batana!"

"It’s the chudail’s bone! Don’t tell anyone or it won’t heal!"

I nodded tearfully. At a small stream, we washed the wound. But by next morning, it had festered. My mother spotted my limp and dragged me to the dispensary.

When the doctor asked how it happened, I confessed. Everything. The milk. The note. The chudail.

My mother turned red, torn between horror and laughter. The doctor burst out laughing.

"So she didn’t become a buffalo?"

“No,” I mumbled. “Because I told the secret.”

Goga never got his magical milk tap. And his mother remained quite human. But whenever I passed that clearing in the forest, I always felt a strange shiver.

Maybe the chudail had read our note. Maybe she was still deciding.